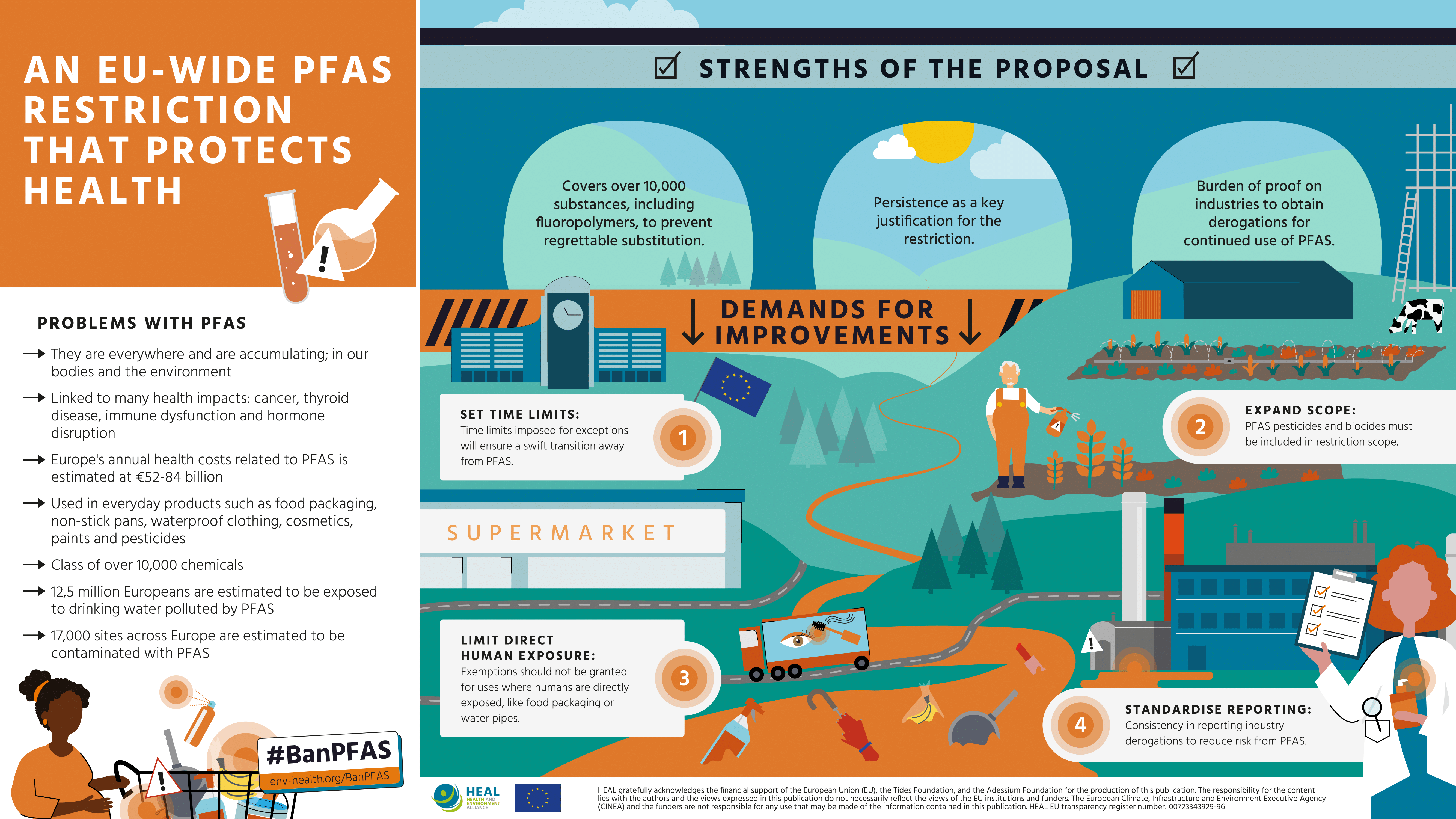

You may not recognize the name PFAS, short for per and polyfluorinated alkyl substances, yet it is likely you come in contact with this toxic chemical on a daily basis. From frying pans and cosmetics to paper food packaging and clothing, PFAS is a class of more than 10 000 widely-used, man-made chemicals. And they are putting our health and the environment at serious risk.

PFAS have been used in a wide variety of consumer products due to their water and stain repellent properties. The chemical group, which includes the more well-known perfluorooctanoid acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), have been used in firefighting foams, non-stick metal coatings for frying pans, paper food packaging, creams and cosmetics, textiles for furniture and outdoor clothing, paints and photography, chrome plating, pesticides and pharmaceuticals.

Visit HEAL’s new website: The impact of PFAS pollution on affected communities across Europe

PFAS are putting our health and the environment at risk

Yet despite being seemingly all around us, very little is known about which specific PFAS are used in which applications and at what levels in Europe. A majority of PFAS are either not covered by European legislation or are excluded from registration obligations under European flagship chemical legislation, REACH. An analysis from the Nordic Council of Ministers showed national product registers are also unable to tell us how PFAS are used, despite the chemicals being detected in environmental samples.

What we do know is that PFAS are very persistent chemicals, accumulating in our bodies and adding to our total daily exposure to chemicals. PFAS are routinely detected in human breast milk across Europe.

Increasing scientific evidence has linked exposure to PFAS to a number of serious health impacts such as:

- lower birth weight and size

- reduced hormone levels and delayed puberty

- decreased immune response to vaccines

- thyroid disease

- liver damage

- kidney and testicular cancer.

Especially vulnerable population groups such as children and the elderly are at risk.

PFAS also accumulate and persist in our environment, with the ability for long-range transport far from the emission points. The chemicals have been detected in air, soil, plants and animals across Europe. Production and use of PFAS have been the main sources of environmental contamination linked to these chemicals. Emissions into the environment take place via waste water release and emissions into the air (which also contaminate the soil and water).

Local communities, instead of actual polluters, are paying the costs

The economic and societal costs resulting from PFAS exposure are enormous. According to a recent estimate from the Nordic Council of Ministers, the annual health costs related to exposure to these chemicals range between at least 52 and 84 billion euros for European countries alone.

Local communities are especially affected by the production of PFAS chemicals. In Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands, the use of PFAS has led to contaminated drinking water around factories. In Germany, Sweden and the UK, studies have shown areas around airports and military bases to be affected.According to the Nordic Council of Ministers, some 100,000 sites across Europe are potentially emitting PFAS.

The story of Italy’s Veneto region

In almost all cases local communities, not the manufacturers, are the ones paying the price for the pollution, with their own health and through taxpayers’ contribution to public budgets used for decontamination (of water notably). The Veneto region in North-East Italy is an example of how PFAS has raised major concerns for towns and cities across Europe. As a result of activities from a local chemical producer, groundwater, superficial waters and tap water was found to be contaminated with PFAS.

Dr. Laura Facciolo, mother and scientific advisor of the Mamme No PFAS group and living in the Veneto area, explains: “The economic price of ensuring our community has clean drinking water without PFAS is huge. Water filtration systems, a health surveillance plan and future building projects for new aqueducts will need to paid for to make sure our water is safe. These costs should be paid for by chemical companies and not by the public.”

“The people of Veneto are an example of the links between PFAS and PFAS-related diseases. We are looking at scientists to publish more research, and to policymakers to make sure a disaster of this scope doesn’t happen again by implementing laws to block the release of toxics into our environment.”

“Dark Waters”: the true story about one of the largest cover-ups in American history

In the USA, environmental attorney Robert Bilott has spent fifteen years in legal battle against DuPont, one of the world’s largest chemicals corporations, because of PFAS contamination. His story began in 1998, when he was contacted by a cattle farmer from West Virginia who believed that the chemical company was responsible for destroying their fields and killing their cattle by dumping toxic waste in the area. His story has since been translated to film – the movie ‘Dark Waters’ – which was screened in Brussels on February 4th 2020, ahead of the European launch of the movie.

In March 2020, HEAL joined up with ChemSec, the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), CHEM Trust and THINK-Film to publish a briefing explaining the problem of PFAS in Europe.

“Early warnings, late lessons”: bis repetita

International and EU regulators have been moving too slowly to prevent and reduce PFAS pollution. Few of the well-known long-chain PFAS are slowly being regulated, but they are being replaced by shorter-chain alternatives that raise similar concerns in terms of health and environment impacts.

“States have a duty to prevent exposure. Every state has multiple binding human rights obligations that create a duty to take active measures to prevent the exposure of individuals and communities to toxic substances.” – Baskut Tuncat, United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights and hazardous substances and wastes, at the 74thsession of the UN General Assembly (October 2019)

In this regard, PFAS are illustrative of the current loopholes in current chemicals regulations: instead of regulating entire families of chemicals together, substances are currently being evaluated one at the time. There is furthermore a tendency to replace harmful substances with other chemicals with similar properties, leading to “regrettable substitution”.

Only PFOS and PFOA, the most well-known long-chain PFAS, are listed under the Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants (POPs), implying that parties to the Convention (which includes the European Union) should ‘eliminate production and use’ of these chemicals.

At EU level, some PFAS chemicals such as HPFO-DA (commonly referred as GenX, from the name of the technology it uses), PFOA and PFBS have been identified as substances of very high concern by ECHA. Others, such as Perfluorohexane-1-sulphonic acid (PFHxS) are currently being considered for restriction. But these actions pale next to the 4,700 chemicals in the PFAS family yet to be regulated.

Genon Jensen, Executive Director of the Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL) said: “Local communities across the world, including those closer to home in Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands, are facing serious health impacts as result of their exposure to PFAS. This demands a direct and game-changing response from policymakers. The Green Deal and Zero Pollution promise are an opportunity for the European Commission and member states to walk the talk and strictly regulate PFAS.”

But there might be opportunities for change on the horizon. In June 2019, European environment ministers called on the European Commission to develop an action plan to phase out all non-essential uses of PFAS. In December 2019, the Netherlands announced its intentions to develop a comprehensive restriction for all uses and products of PFAS, except where essential. Denmark, Sweden, Norway and the European Chemical Agency have indicated their willingness to support such a restriction. If going through and properly crafted, it could be an important game-changer to prevent further PFAS pollution and related health damage in the future.